History reveals the creation of RSJ

Bluedevilhub.com Staff–

The projector at the front of the class shows an early 20th century political cartoon: a tall man with a caricatured “savage” on his back. He is dragging the dark-faced, white-lipped “savage” to a schoolhouse. The caption reads,“The White Man’s Burden”.

A few days later in the classroom next door, social studies teacher Fern O’Brien plays a video about the Panama Canal highlighting race relations during its construction. Most of O’Brien’s students watch attentively. Later in the period, the class examines early 20th century political cartoons, discussing the racist attitudes they illustrate.

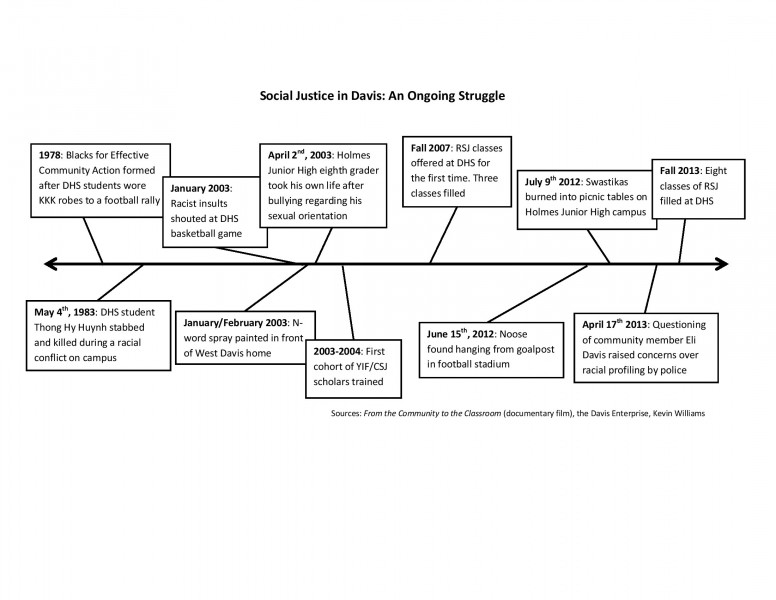

The RSJ classes were created following a string of racial incidents at DHS incidents that made the community question whether it was really as open-minded as it claimed to be. Now, six years later, there are eight sections of RSJ at DHS.

In 2003, a few DHS students shouted racist jeers such as “We go to college, you go to jail” and “Who’s your baby’s momma?” during a Davis versus Fairfield basketball game. Fairfield player Ian Blair described the incident in the documentary film “From the Community to the Classroom,” produced by a group of students in 2007. Blair compared what he faced in the DHS gymnasium to the discrimination Jackie Robinson encountered on the baseball field in the 1940s.

A few weeks later, the n-word was spray-painted in front of a black family’s home. Public outcry resulted in a series of community forums, where some students from the Davis school system came forward and revealed that they faced racism from some of their classmates.

As a result of these revelations, a group of students from a variety of different backgrounds were brought together to investigate further. These were the Youth in Focus/Catalyst for Social Justice (YIF/CSJ) scholars.

Dr. Jann Murray-García is a pediatrician and president of Blacks for Effective Community Action. She helped spearhead the YIF/CSJ effort.

“Adults were saying, ‘We’re at the end of our rope, what are we going to do?’ We tapped into the expertise of youth,” Garcia said.

The YIF/CSJ scholars conducted surveys of DHS students. They resulted in more than 60 percent of black and Latino students reported feeling that their classmates and teachers expected them to do worse in school than other racial groups. These findings corroborated what many non-white students had said during the community forums.

“[When the results first came out,] there was a lot of defensiveness, unwillingness to hear what we said. People thought we should not have riled up the students,” Tessler said.

The YIF/CSJ scholars continued advocating for change. Research findings were shared with the Davis community through presentations. A second and third cohort of YIF/CSJ scholars underwent training. And in 2007, the RSJ classes were established at DHS.

“There’s a lot of denial, and it gets in the way. When […] the hate crimes happened, people would say, ‘Oh no, these can’t be Davis kids; they must be from Woodland or something.’ [The purpose of RSJ is] not just having information but hopefully to be personally changed. That was our hope—not just a graduation requirement, but transformational,” Garcia said.

The first year, in 2007, teachers and counselors worried they would not get the 29 students that were needed to form the class. There ended up being enough students for three classes of RSJ, and another class has been added each year.

But on June 15, 2012, a noose was found hanging from the goalpost in the DHS football stadium. The incident introduced a whole new generation of students to the racial tension beneath the surface of DHS.

“There’s always going to be idiots not understanding the implications [of their actions]. There’s still racism, there’s still bigotry,” Tessler said.

However, García remains hopeful.

“I was more encouraged by the response from the mayor and the school district than discouraged by the news. Make sure that there is a strong response […] hate thrives with silence,” Garcia said.

Williams discussed the noose incident with his 2012 RSJ class right at the beginning of the year.

“We talked about it a lot; not so much as an event, but why we need a class like this,” Williams said.

Many students in RSJ classes this year signed up out of a desire to learn more about the role race plays in their school.

“I chose to take [RSJ] because there have been a lot of racial things [at DHS]… I’m interested to learn more about what’s the root of the problem,” junior Kenya Oto said.

Junior Angie Deng, a student in Williams’ RSJ class, took the class for a different reason

“I thought it’d be interesting to learn about history from the minorities’ point of view, not history written by the winners. I thought we didn’t have any problems [in Davis,] but now I realize it’s only because I wasn’t a part of the minorities,” Deng said.

Tessler believes there is still a lot of educating to do in America and “this step is very important”.

“We still get parents who will call and say, ‘I don’t want my kids being with those kids,” Tessler said.

Junior Mauricio Rocha is also taking RSJ.

“I chose it because I want to be more understanding of other races and how they feel,” Rocha said.

García is proud of how far the RSJ classes, eight of them now, in 2013, have come.

“I think they [the CSJ/YIF scholars] felt like, ‘Wow, besides the data we got, everything we learned about race, how to not have it be taboo—every student should be able to do that [and] grow with each other. Everyone should have that experience. It can be really hurtful learning about [history], but that’s the best way not to repeat it. The truth sets you free,” Garcia said.