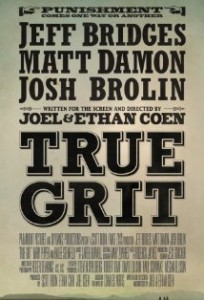

True Grit Review

The poster blares “PUNISHMENT COMES ONE WAY OR ANOTHER,” but the Coen Brothers’ new film True Grit is a much more subtle film than advertised, with a few scalding flaws.

It’s an almost absurdistly gothic world, full of barren landscapes, with the odd bearskin-donning wild man, and a color palate limited to dark brown, yellow-tan, and the odd grey. It’s late-1800s rural Arkansas, a land where people speak their minds and apparently have no concept of speech contractions.

Overall, one gets the sense of some darkly beautiful painting. But through all of the style and design comes a solid story.

Fourteen-year-old Hailee Steinfeld gives off a wonderfully brusque sensibility as Mattie Ross, a forthright and precocious young girl, seeking justice for the cold-blooded murder of her father by their farmhand, Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin). She enlists the help of the drunken, elderly, and trigger-happy U.S. marshal Rooster Cogburn to catch Chaney, as they make their way through the empty winter landscapes of the Choctaw Nation.

They are joined by Texas Ranger LaBoeuf, who is also hunting Chaney (though for the murder of a Texan senator). It’s a relatively small role for Matt Damon, but he plays it beautifully, with wonderful attention to detail.

His LaBoeuf tries to strut around, though mostly unsuccessfully with Mattie’s needle-sharp tongue ready to burst his bubble, as he boasts about his prowess as a tracker (up to and including the mandatory tale of drinking from a horse’s hoof print). Damon’s LaBoeuf is one to be laughed at, but in a realistic, fleshed-out way. No cartoons here.

But sadly, the same cannot be said of what is really the anchor character of the plot—Rooster Cogburn. The gruffness, humanity, and depth found in the character of Rooster Cogburn are almost unparalleled. Bridges’ performance does not, in this reviewer’s opinion, do the part justice.

Specifically, Jeff Bridge’s overplays one of the greatest characters in film history by rendering him such an over-drunk buffoon he is either completely unintelligible, or on the brink of it. The unintelligibility could be overlooked, given the fact that Bridges’ character does maintain a high level of intoxication throughout the movie, if it wasn’t for his performance’s unlucky juxtaposition with that of Damon’s. Damon is able to maintain a realistic Texas accent and a believable speech impediment, all the while still managing to make himself understood, and his role, though comic, not that of a clown.

Rooster Cogburn is this movie’s Heartbreak Hill.

The Coen’s swear they didn’t watch the 1969 True Grit, and though it’s fantastic they didn’t sink so low as to try and recapture the magic of a great movie, Jeff Bridges simply doesn’t know what to do with himself.

His solution is a compromise where Cogburn is a big drunk teddy bear from start to finish.

But without a hard-shelled beginning, the audience misses out on seeing character development. This film tries to surpass the 1969 version, and in many ways it does. But it’s missing the gruffness, the bite that only the Rooster Cogburn character can provide.

(Maybe Bridges’ did a better job than it seemed, but the answer would most likely lie in the dialogue, and unfortunately, one would need subtitles to decode the drunken mumbling during what one can only assume were the key scenes.)

But through a few off-notes, there is still a beautiful, intelligent film. Though the Gothic rural landscape is not particularly original, given the violence (particularly a scene where Cogburn debates about whether or not he should let LaBoeuf to try to mend his near-severed tongue, or save him the trouble and yank it right off), it is at times a dark film.

Steinfeld’s Mattie Ross, in conjunction with LaBoeuf, provide the rays of sunshine that save the audience from drowning in images of softly swirling Arkansan snow.

There are also measured doses of humor that alleviate the film from being too dark, but not on the level that one would expect from the makers of Raising Arizona. Genuine intelligent humor comes across even in the Coen Brothers darkest movies (Fargo), though here it’s vaguely apparent in only a few minor characters. Mostly the dumb petty crooks and a few disenfranchised minorities, and all, again, with a healthy dose of violence, which of course falls right into Coen Brothers form.

The largest failure in the humor department, and the fish-out-water element for the Coen’s (though they have overall succeeded with the movie), is that it seems that this is not a movie of dumb people. Yes, a few of the main characters make fools of themselves (i.e. the drunken Cogburn), but they’re stilling firing on all cylinders.

Or, to fit with the setting, they’ve got all the spokes required to make an exceptionally functional wagon wheel.