Working against teens’ internal clocks

By Kira Furie,

HUB correspondent–

How early school start times affect education

A typical school day

Emily Kappes’ alarm sounded at 5:30 a.m. She continually hit the snooze button, and once she finally looked up at her alarm clock, the numerals 6:30 stared back at her. Knowing she needed to be at school at 7:45 a.m. Kappes ran around, trying to get her things together– stressed, dizzy, and tired.

The sophomore had been up until midnight studying for her AP Chemistry test the following day, which, according to her, she did only okay on. She made careless mistakes and was having a hard time remembering information. “I couldn’t perform as well because I was exhausted,” Kappes said.

Adolescent sleep needs

According to an online resource published by the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School, “without adequate sleep and rest, over-worked neurons can no longer function to coordinate information properly, and we lose our ability to access previously learned information.”

The National Sleep Foundation says that teenagers need 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep per night. Research included in “Adolescent Sleep Needs and Patterns” shows that adolescents don’t naturally fall asleep until 11 p.m. or later due to the shift in their internal body clocks. If you do the math, this would mean that they would need to wake up at 7:30 a.m. to get 8.5 hours of sleep.

According to Helene Emsellem, the director of the Center for Sleep & Wake Disorders at George Washington University, it is nearly impossible for high school students to get an adequate amount of sleep with the early high school start times and the shift in their internal body clocks.

A later school start time

To compensate for this issue, Emsellem suggests a school start time of 8:30 or 9 a.m.

“If our goal is to educate, then we have to think about what the best time is to educate and how much sleep is necessary for that,” Emsellem said.

Kappes independently stated 8:30 a.m. as her ideal school start time because it would allow her to get enough sleep, rather than her usual five to seven hours, and still have time for extracurricular activities. She feels that this start time would end her issue of always running late in the mornings.

Fatigued first period

English and Speech & Debate teacher Janine Widman only has tardy issues in her first period class. “I feel like there’s less of an eagerness to learn and to put for effort,” she said.

She also notices a similar problem with her two teenage daughters in the mornings. “My kids are comatose in the morning,” Widman said.

Social sciences teacher Katie Wi has also noticed that her first period class is the least talkative and most dead of all of her classes. According to Wi, all other DHS teachers she has talked to feel the same way.

Science of sleep

Wi, who learned about the importance of teen sleep while getting her teaching credential, doesn’t understand why school begins so early.

Phyllis Payne, the co-founder of the organization SLEEP (Start Later for Excellence in Education Proposal), stands behind the science in this matter as well. “I believe that the quality of life and learning experiences for high school students and their families would improve with a healthier school schedule– one that matches the teen body clock instead of working against it,” she said.

The information that is taught to you during the day isn’t actually learned or ingrained in your brain until you sleep according to Emsellem. She finds it problematic that the point of school is to learn, but students aren’t being given that optimal opportunity.

Craving sleep

The National Sleep Foundation research considers sleep to be food for the brain. “When hungry for sleep, the brain becomes relentless in its quest to satisfy its need,” the report said.

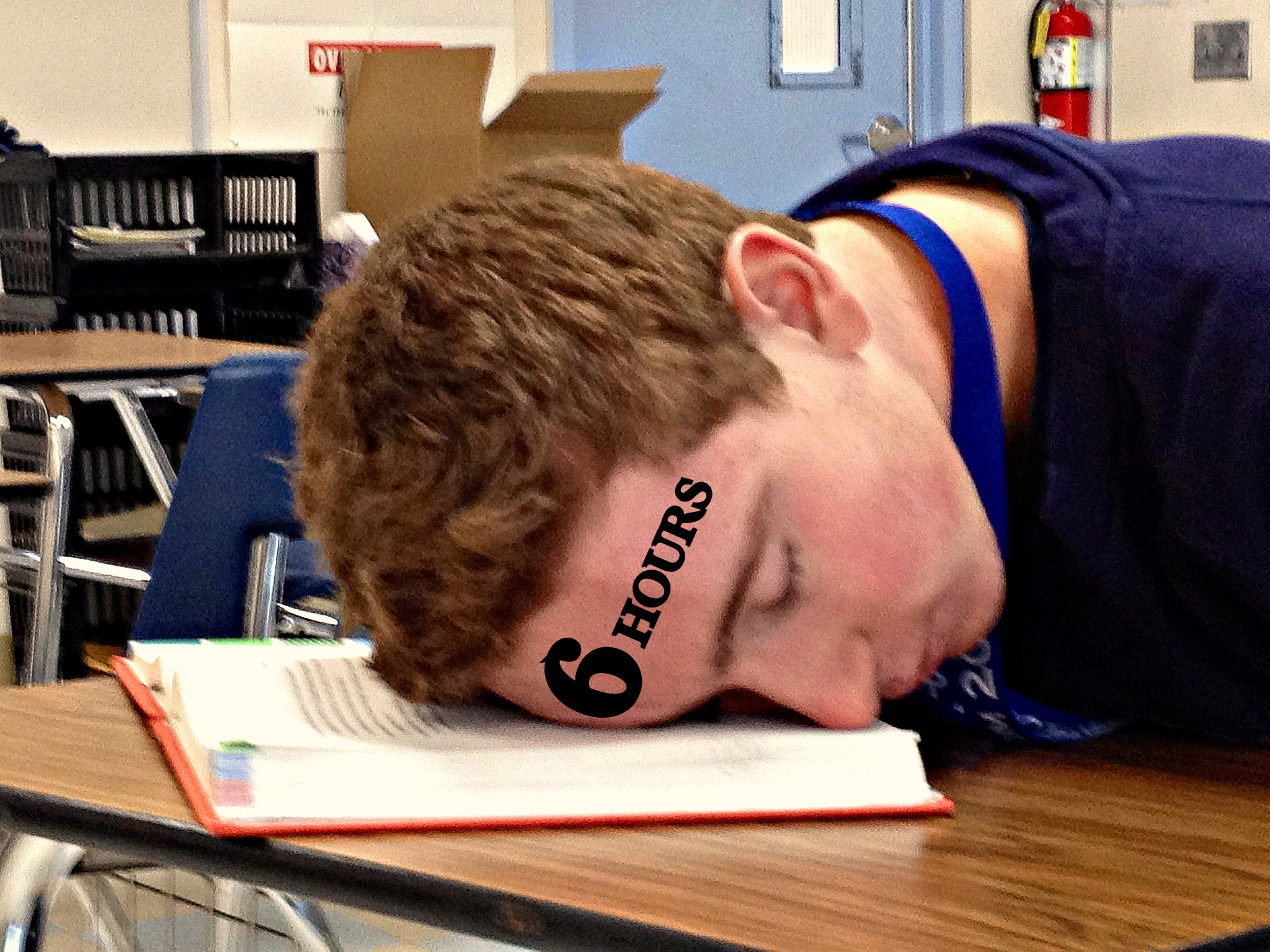

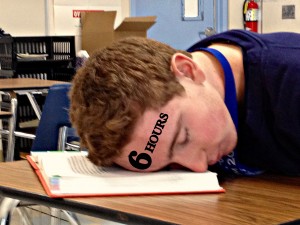

Some students, such as junior Jacob Muller, are sleep deprived to the point that they cannot resist the temptation to sleep in class.

“I’ve never not been tired in school,” Muller said.

According to Muller, he has a reputation among his peers for sleeping in class, but still managing good grades.

“It’s a constant struggle because you’re sitting there, trying not to blink, but once you have one long blink, it turns into a longer blink, and then you’re out,” Muller said.

Although some people believe that students just aren’t dealing with what’s on their plate, it’s something they really can’t help, Emsellem said. “It’s like asking adults to wake up at 4 a.m.”

Making a change

Both Emsellem and Payne thought that knowing the science that links sleep to a good education would convince schools to make a change, but they both find it to be a slow-moving process.

“I think it’s very important for the students to get involved—sign petitions, talk to counselors, and try to change [the early school start time],” Emsellem said.

According to Susan Lovenburg, the Davis Joint Unified School District School Board vice-president, there has been no change to the DHS bell schedule in more than ten years. There has also been no talk of changing the school start time since she was elected, which was in 2007.

“Should the process begin again, it would start with the principal and involve consultation with staff, students and parents. Their recommendation would then be vetted by the Superintendent for alignment with law, collective bargaining agreements and [School] Board expectations,” Lovenburg said.

Countering the Myths

There are many students and teachers who fear that a later start time would be counterproductive for two reasons: it would take time away from sports and students would just go to bed later.

Sophomore Matt Whittle is one of these students. He has swim practice six to seven days a week, and worries that school ending later would give him less time to swim and do homework.

“It would just be pointless,” Whittle said.

Nonetheless, according to Phyllis Payne, the co-founder of the organization SLEEP (Start Later for Excellence in Education Proposal), Loudoun County, Virginia now has a school day from 9 a.m. to 3:50 p.m. and they have found a way to fit sports and other extracurricular activities into their schedule. “I’ve heard from parents and students there who say this time works best for them,” she said.

Kian Reno wouldn’t want school to start later either for the sake of sports. Reno has a free first period because his mom made him after reading a book about sleep deprived teenagers.

Reno couldn’t imagine having a first period. “When I’m tired I don’t have the energy to participate in all the activities we’re supposed to do [in class],” the sophomore said.

“It does take some juggling of the schedule to keep everyone in the school system happy,” Emsellem said, acknowledging it can be seen as difficult to allow for both sufficient sleep and sports.

What most people don’t realize, according to Emsellem, is that, along with helping academic performance, sleep helps sports performance as well. “If you look at the schools who shifted to a later start time, they’re the ones with the winning [sports] teams.”

English and Speech & Debate teacher Janine Widman considers 8:30 a.m. as her ideal start time, but worries about how this would affect the productivity of students’ days. She thinks that students may just stay up later and as a result not get any additional sleep.

“We know that with later morning start times teens DO SLEEP MORE! It’s a myth that students will just stay up later — they don’t,” Payne said in an email interview.