LGBT WEEK: Epithet use in society

By Katrina Sturm and Lauren Wienker,

Bluedevilhub.com Staff–

The n-word appears in rap song after rap song. Queer is now an accepted term in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community. The b-word becomes less insulting, to some women, each day.

Words are a constantly fluctuating part of our culture, and it’s this never-ending change that confuses many.

With epithets like the n-word, there is often confusion as to how appropriate they are because of the differences in the way people from different backgrounds, ages, and races use or perceive the word.

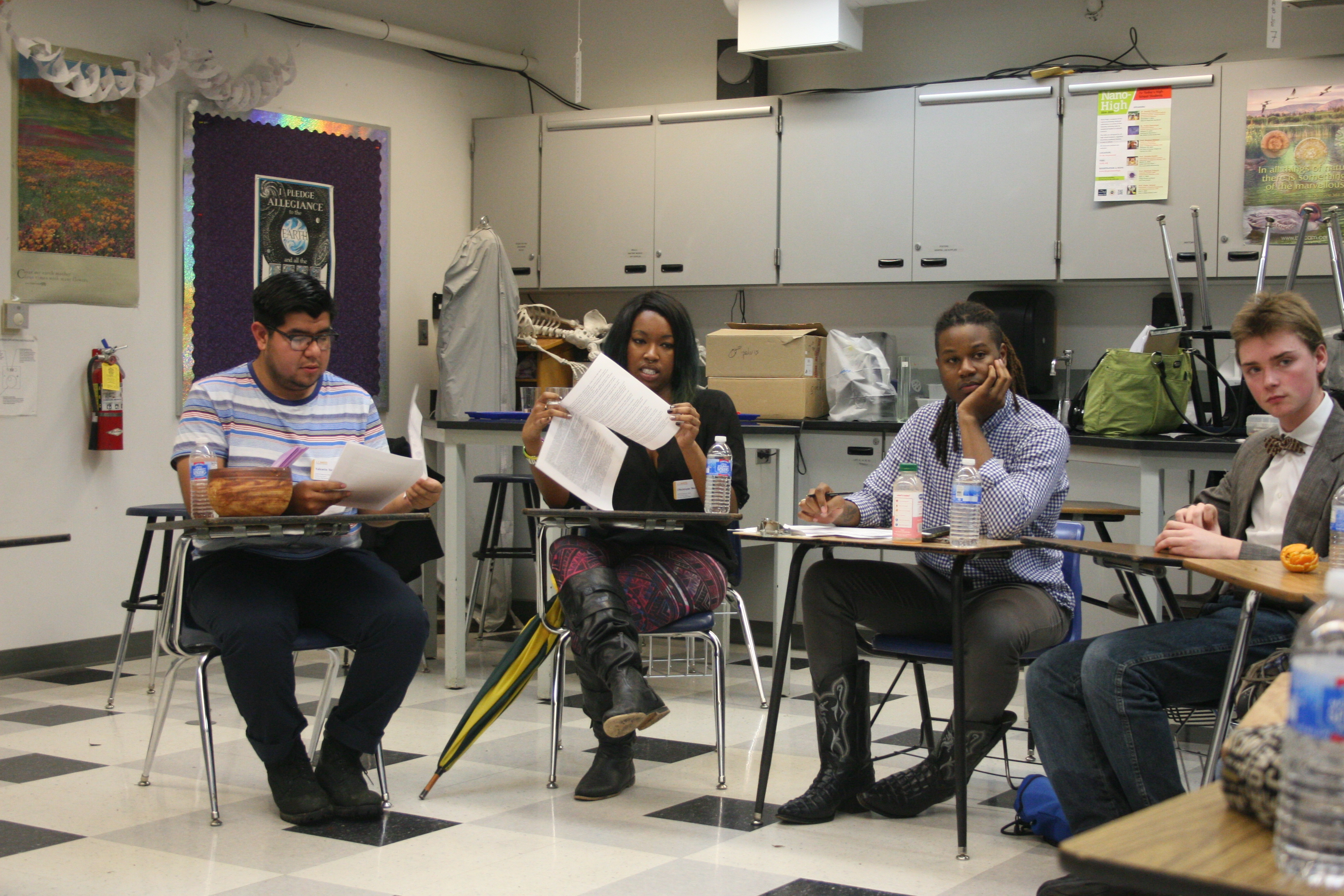

Monique Merritt, a student assistant from the UC Davis Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Intersex and Asexual (LGBTQIA) Resource Center, came to Davis High on Dec. 3 to meet with actors from Acme Theater Company and other interested parties. She discussed issues relevant to the theater company’s upcoming production of “Stop Kiss,” a play that features a couple’s recovery from a hate crime.

“I think that [the n- word and other epithets] still maintain the same meanings, connotations and histories as always, but I […] [think] their usages have changed,” Merritt said.

Use of the n-word was discussed at the meeting along with issues that are faced by the LGBT community which will be featured in “Stop Kiss.”

“Many [people] are under the impression that the n-word is synonymous with “friend,” “homie,” et cetera. While I agree and am aware that people use the n-word to mean those things, I think that there is an inherent history attached [to the word] which is why black people [only] use it with one another,” Merritt said.

The n-word has been used as a tool in the systematic oppression of people of African descent for a very long time, according to activists.

Chaz Walker-Ashley, assistant director of the UCD LGBTQIA Resource Center, also attended the December 3 meeting at DHS, and expressed the same belief that Merritt did: non-black people should not use the n- word.

“I’ve come to understand the ‘in-group and out-group’ rule,” Walker-Ashley said. “When it comes to understanding reclaiming of derogatory words, those who identify [with] a particular community have the right to use a word that may be not appropriate for those outside of the group.”

History teacher Kevin Williams sits on the corner of his desk, facing a classroom half filled with students. While changing slides on a PowerPoint designed to help students study, Williams explained that he believes the use of the n-word is “really controversial within the black community itself.”

“ [This is] true for other slurs [as well],” Williams said.

“ […] Somehow people think it’s OK if they [identify with a community…] like ‘I’m black it’s OK for me to say this,’ ” he added. “The more it’s out there the more damage it does.”

The n-word and other epithets abound on social media sites. These epithets are seen so often that they may be perceived as harmless.

According to social media tracking service Topsy.com, on Dec. 7, 2014 the word n***a was used more than 500,000 times on Twitter. The same day, n***er was used 5,000 times.

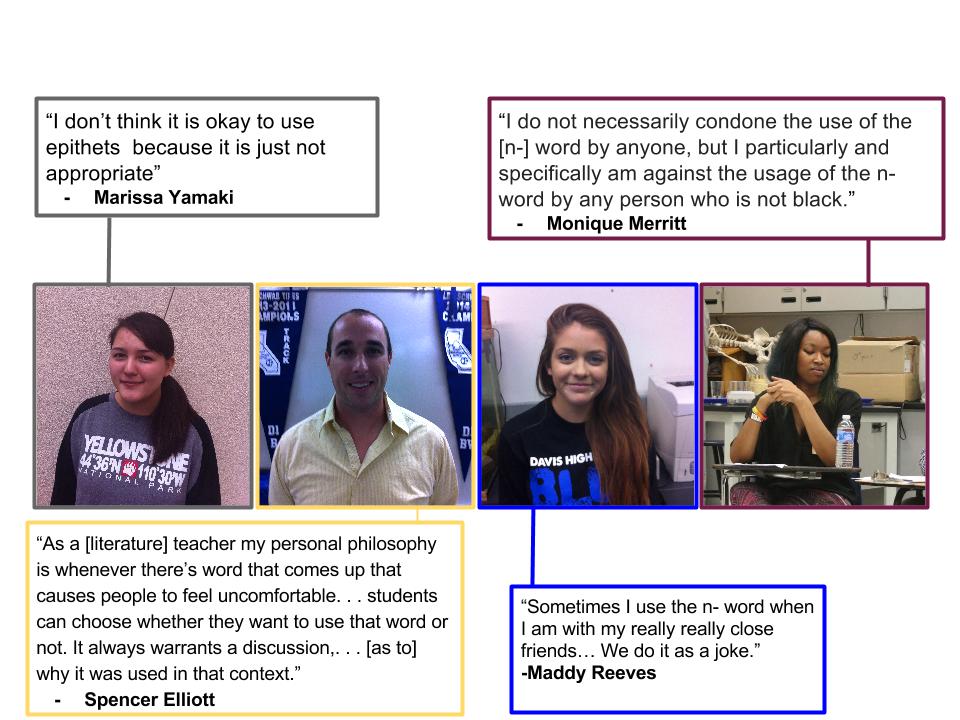

For English teacher Spencer Elliott, there are specific circumstances under which the use of the n-word is permitted.

“The n-word appears frequently in “Huckleberry Finn,” which is part of the eleventh grade curriculum,” Elliott said.

“Whenever there’s a word that comes up that causes people to feel uncomfortable […] students […] can choose whether they want to say that word or not,” he said.

Elliott explained that allowing the use of the word has a lot to do with keeping the integrity of the piece of literature being read.

Part of the issue is that there are two distinctive spellings of the n-word, and that younger people often consider them separate. N***a and n***er are used very differently. To some, the word n***a is used as a term of endearment or friendship, while n***er is more derogatory.

To solve this problem, many believe that schools should take the initiative to educate student about what these controversial words really mean.

“In short, education and a lack of courageous dialogue in a safe environment keeps the use of that word alive […]” said Jann Murray-Garcia, a Davis parent and pediatrician who helped start the Race and Social Justice (RSJ) class at DHS.

“Ask anyone who has taken RSJ how comfortable they feel about slinging around the n-word, or what they feel when they hear it.” Murray-Garcia said.

“Education! We need to drill into people’s heads from a young age that these words are extremely hurtful and affect more than just the victim. Teaching the histories behind epithets and teaching tolerance for our differences will help achieve that,” sophomore Jackson Laird said.

“Since I have come out I have never been called a slur,” Laird said. “But before I came out I had been called a slur a couple times. They weren’t actually accusing me of being gay, but it still hurt because I knew I was gay.”

Eric Russell is an Associate Professor of French at UC Davis and teaches classes on taboo language. He believes that teens know that using “taboo language” is wrong, but do it for the same reason that they rebel against other social norms. Even children who are only five-year-olds know that there are words that they are not supposed to use because they are “bad” words, according to Russell.

“All words change, in form, meaning, connotation, association, et cetera, because they are constantly being transmitted and recreated by users,” Russell said. “So there is nothing surprising [or] even particular about the changes to the ‘n-word’; it just happens to be one that is, at times […] used to insult people, based on perceptions of their ethnicity. […] For this reason, like all such words, it is rather ‘loaded.’ ”