ELL students benefit from new bilingual paraeducator

By Lev Farris Goldenberg,

BlueDevilHUB.com Staff–

English language learners, some arriving in the U.S. as recently as this September, have limited options when it comes to getting help with school. English is their second or perhaps even third language for these students, and some of them come here knowing none at all.

Stephanie Guzman is the only bilingual paraeducator at Davis High. However, the school did not get her much-needed help until last year.

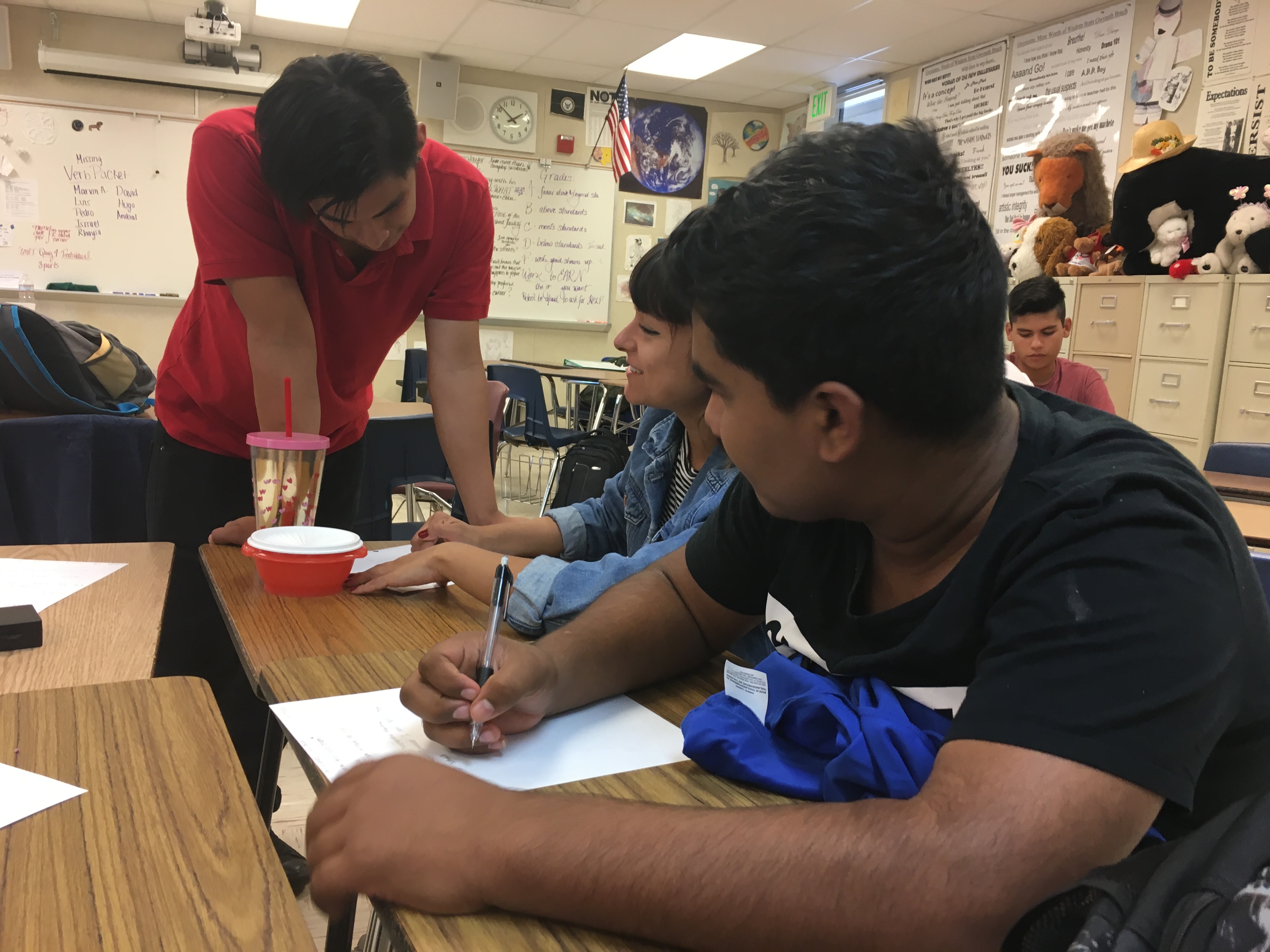

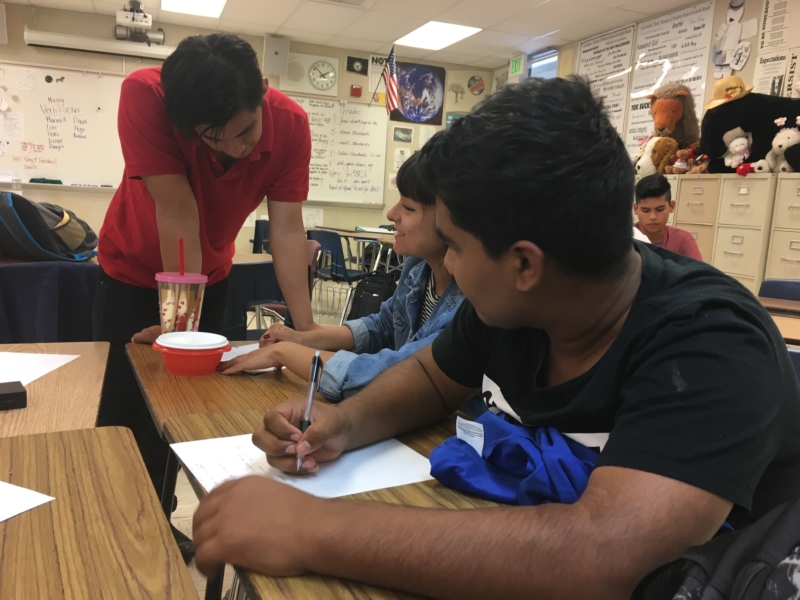

Her job is to help the 70 to 90 ELL students, whether it be with translation, classwork, understanding a teacher’s instructions or anything else. Guzman sits in on mostly English and history classes, one each period, including Gwyneth Bruch’s sixth period ELL class.

One Wednesday, the students were working on writing conversations in English that they would present to the class another day. Guzman went around helping students compose sentences and situations, and it is not hard to tell she is stretched thin.

So many kids needed help, and Bruch can not always translate. (My elementary school was Cesar Chavez Elementary, so I am fluent in Spanish as a result of the Immersion system. I sat in on the class for this story, and I ended up spending half my time helping my peers with their classwork and translating.)

Bruch’s class is conversational English, while David Achimore, the head of the ELL department, teaches the writing and grammar classes for English learners.

There are different levels of EL students. They range from levels 1-6 ,and each year students are placed in one of the categories. Achimore said it is hard to even differentiate many of the kids on levels five and six from native English speakers.

“EL students just as right of a reason to be in AP classes as anyone does. A lot of our EL students are in BC Calculus and they’re doing quite well, because there a wide range,” Achimore said.

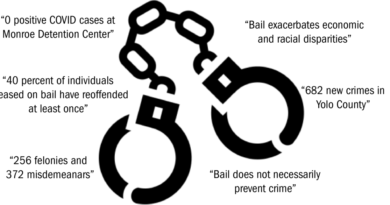

Achimore also knows how valuable bilingual paraeducators can be. A couple years ago, 11 percent of students on the whole campus were on the D and F listーwhich means failing two or more classes per semesterーas were 37 percent of EL students. Achimore says once they got Guzman and the Academic Center involved, that number fell from 37 to 23 percent within the last year.

“[Guzman’s] great, and she doing a lot, but she is definitely being asked to do quite a bit,” Achimore said.

The Academic Center (AC) can also be a huge help to ELL students. Most of the tutors from UC Davis in the AC are bilingual, and their second language– or first in many cases– is Spanish. Spanish speakers make up more than half of all ELLs.

“[The UCD tutors] don’t start until [UCD] starts […] so the first month of school for ELLs, which is probably the most important, [they have] the least amount of support, which is a huge problem,” Achimore

Achimore has advocated for more bilingual paraeducators but, “We just don’t have the money in the district to do that.”

Senior Iesha Anderson is the teaching assistant for one of Bruch’s classes, and she sees the day to day challenges faced by ELLs.

“I feel like the teachers should try to do something, not go out of their way completely, but do something to assist with the Spanish speaking students or the students who don’t speak english. But they don’t really try. They just send them off to the AC, and they expect them to learn from the AC and not actually in the classroom, with the teacher,” Anderson said.

While it is true that Achimore encourages teachers to keep ELLs in the class as much as possible, some situations make the AC an invaluable asset. “[ELL students] are a member of the class and they’re trying to learn as well,” Achimore said.

“History classes are so full this year, you’ll have 38 kids with just two EL students, and if they need support, that’s only offered in the [AC]. It does make sense that having them work on that assignment with a one-on-one tutor in the academic center makes more sense than having them in a classroom,” Achimore said.

No matter how you look at it, it is a tough decision. If Guzman is in the class, she can help the ELLs. But she can’t be everywhere at once.

According to Achimore, history classes used to be the most failed classes for English language students. After hiring Guzman, the bilingual para whose focus is history, it is no longer history, but science classes which are the most failed by ELLs.

“My goal is to get a bilingual para for science classes,” Achimore said. He tried to fight for one last year, but once again, “The funding just isn’t there, we’re struggling just to keep class sizes low.”

Unfortunately, the funding might never be there for more bilingual paraeducators.

“I think the district has realized how important they are,” Achimore said.

History teacher Peter Reilly has more than one ELL in some of his classes.

“I’m not saying that you just throw money at things, you have to be really calculating about,” Reilly said.

One of the solutions is differentiating the curriculum where teachers create alternate curriculum specifically to engage and facilitate learning for ELLs. But that can be tough for teachers because of the large class sizes.

“If you have seven different languages in a class, and seven kids at seven different levels, you’re talking about really, seven different classes. And how does one teacher do that?” Reilly said.

If these students do not receive the proper help, it can can become a chain of destruction.

“Usually with language, what happens is, kids who are unfamiliar become insecure. Then, they start feeling like they’re not the smart kid. Then, they get behind, and that is not just one class, it is six classes,” Reilly said.

Although history class grades for ELLs are improving, Reilly still faces some unique obstacles.

“These kids when they come here, they may be brilliant in math and science, because that’s a universal language, right? Well, […] I teach government, how do you access the words like ‘expressed powers’ or ‘filibuster?’ ” Reilly said.

Reilly heaps praise on the work Achimore has dedicated himself to.

“[Achimore] does incredible things with these kids,” Reilly said.

But Reilly reserves his highest praise for the ELLs, considering the huge obstacles they face each day they come to school.

“It is daunting. It’s the history of our country though, you got to remember. Immigration issues, from day one we’ve been a country like this. So that is why I look at these kids that are doing this and I go, ‘Wow, that’s really brave,’ ” Reilly said.

DHS teachers aren’t the only ones who recognize the struggle. Findings in the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) report show recognition of the problem.

The report from last year stated, “A notable gap exists between the scores of Asian and white students relative to the scores of Hispanic/Latino, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and English learners and the school wide average is relatively consistent between years.”

The same report also said that “while not all numerically significant, the low proficiency percentages of subgroups including black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, English learners and students with disabilities does present cause for concern.”

The report notes that programs including the AC, ACES classes and AVID can do wonders for ELLs. The main progress has been, “more consistent instruction and curriculum.”

They seem to be on the right path; according to the WASC report, in the past four to eight years, teachers of English Language Department courses have been consistent and the curriculum used has been the same (Edge materials), as well as the school also obtaining Spanish versions of the textbooks in the new common core math curriculum.

“A lot of common core math now which is word based. […] In the past I think math was something EL students felt a bit more confident about, now that is so language heavy. Which is a good thing, that they’re still getting language practice in math,” said Achimore.

But again, it comes down to class sizes. Déjà Vu, anyone?

“We don’t have a bilingual para in there, so it really comes down to the teacher being able to assist them. I’m sure every math teacher is working 120 percent. When I look at the number of EL students who are in classes which are over the maximum, which is supposed to be like 32 or 34, it’s ridiculous,” said Achimore.

Achimore also said there are some common misconceptions about ELL students. One is that, “EL students at the high school are all high level ELs, they’ve been in the country for years, maybe their English isn’t perfect but they’re doing well enough.”

This idea is wrong, however.

“We’ve got something like 20 students who arrived this year at 10th, 11th or 12th grade levels who arrived from a new country,” Achimore said.

Some have a little English already, but most, especially ones from El Salvador and Guatemala are under-schooled.

One, Achimore said, has not been in school since sixth grade and speaks no english at all.

“People forget that the high school actually gets brand new EL students as well. […] I always try to advocate for those kids and make sure they’re not getting lost,” Achimore said.

Another thing that is often forgotten is that many of the students are not Spanish-speakers.

Senior Ali Dehghani speaks some English, but his home language is Persian. Senior Jeng-Gang Wang speaks Mandarin. He has been here two years but it is still hard for him to understand teachers. Junior Hengyuan Liu originates from China, and now struggles to understand his teachers and translate quick enough.

Liu uses an app called Chinese English Dictionary and Offline Translator, made by Xung Le to translate words and lessons, but sometimes it is a struggle to keep up with what the teacher is saying. And sometimes, the teacher does not allow him to use his phone in class, although its purpose is to facilitate Liu’s understanding.

He does not say whether Guzman is in any of his classes to help him. But many ELL students do not have access to Guzman in all their classes.

This is because teachers have contracts that dictate the maximum number of students they can have in a class. This can be an average of all their classes, but many teachers are still over the contract limit. So that means that all the ELL students can’t be in the same periods because there simply are not enough spots in each class.

This results in some classes having the benefit of Guzman there to help, and some classes do not. For example, Achimore said in the case of two fourth period history classes, he was forced to put new students from El Salvador who did not speak any English in the class where Guzman was not.

Reilly summarized the problem with limited support and translation options.

“With a public school, you have to be accessible to all. There’s the physical access, but then there’s the cognitive access,” Reilly said.

He added that EL students make much slower progress at the high school than, say, kids in Spanish Immersion at Cesar Chavez. In that program, students are immersed in a foreign language each year for full days.

At the high school, they have just one or two EL classes per day, and the rest of their periods they are expected to mostly grasp the material and understand the concepts right away.

At Chavez, kids are around five when they start, so their brains were more open and quickly adaptable to new languages.

“What we know about language acquisition, it’s like math, it’s like music, all those those kinds of things that engage the left and right brain,” Reilly said.

Dehghani knows each student’s situation is conditional on many variables.

“In my opinion there are different situations for students to understand foreign languages, and it all depends on their classes and their teachers,” Dehghani said.

Clearly, bilingual paraeducators are a step in the right direction. But, Guzman knows there is no perfect answer.

“It’s hard for me to focus on all the students because all of them need help,” Guzman said.