Students with disabilities prepare for life after high school

After high school, intellectually and developmentally disabled students can have a challenging time adapting. Whatever pathway they take — community college, a career or an inclusive four-year programs—these are people with a lot to contribute.

By Molly Burke and Claire Stevens,

BlueDevilHUB.com Staff–

Disability advocate Beth Foraker calls it “falling off the cliff.”

Though the end of high school is a difficult transition for many students, for students who have had the support of a special education program throughout high school, the transition can be especially challenging.

Beth has four children, including Patrick, a son with Down syndrome. When her son approached the end of his time at Da Vinci High School, she remembers approaching the impending ending of high school with concern. Patrick had to find his next step, whether it be working, community college or something else.

Patrick Foraker: An inclusive environment

When Beth Foraker’s third child, Patrick, was born with Down syndrome, she believed that she and her family would be isolated for the rest of their lives.

“I had this comfort that he was exactly as he was supposed be and I didn’t see him as broken […] I wasn’t sad about that.” Instead, it was the “instant separateness” that Beth felt from the world that saddened her.

Patrick’s early days were filled with health problems. He had open heart surgery at only nine weeks old and suffered from leukemia as a preschooler.

Beth’s older daughter attended Davis Community Church Nursery School (DCCNS), and Beth was shocked when a teacher at DCCNS asked her to consider bringing Patrick to the school when he was old enough. She had feared no preschool would take Patrick.

At DCCNS, Beth observed Patrick mimicking his peers and being able to have the regular preschool experience, mixing playtime and academics.

When he was also offered a spot in a special education preschool, funded by the state with other students who had intellectual and developmental disabilities, Beth and her husband decided to split his time between the special preschool and DCCNS.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) mandates that a child must be placed in the least restrictive environment. Because Patrick had already been involved in an inclusive preschool, it was clear he could continue to be included in preschool.

For Beth, the inclusive environment at DCCNS and, later, St. James Elementary, was key for Patrick.

“We have a deficit mindset for people with disabilities and that is pervasive in education,” Beth said. She found that when Patrick had high expectations set for him, he was able to achieve them. At St. James, he had support from a classroom aide to help him reach these expectations.

Patrick continued at St. James until eighth grade when he was told he would not be able to follow his brother and attend Jesuit High School. This was especially difficult for Beth as she knew other students who had performed lower than Patrick in his class who went to Jesuit.

Beth describes Patrick as a violet, while most people are daisies. “He’s rare. He needs a little more tending. Not everyone knows how to take care of a violet. But he’s a violet living in a daisy world.”

Though it may be a daisy world, “he has no interest in being a daisy. None of us who love him want him to be a daisy. We’re really happy he’s a violet.” Still, he was given tests meant for ‘daisies,’ that he’s never going to do well on.

“I know he is a violet,” Beth said. She’d prefer to instead focus on figuring out how to help him live in a daisy world.

Instead of going to Jesuit, Patrick continued on to Holmes Junior High School and then Da Vinci High School, where he graduated in 2018.

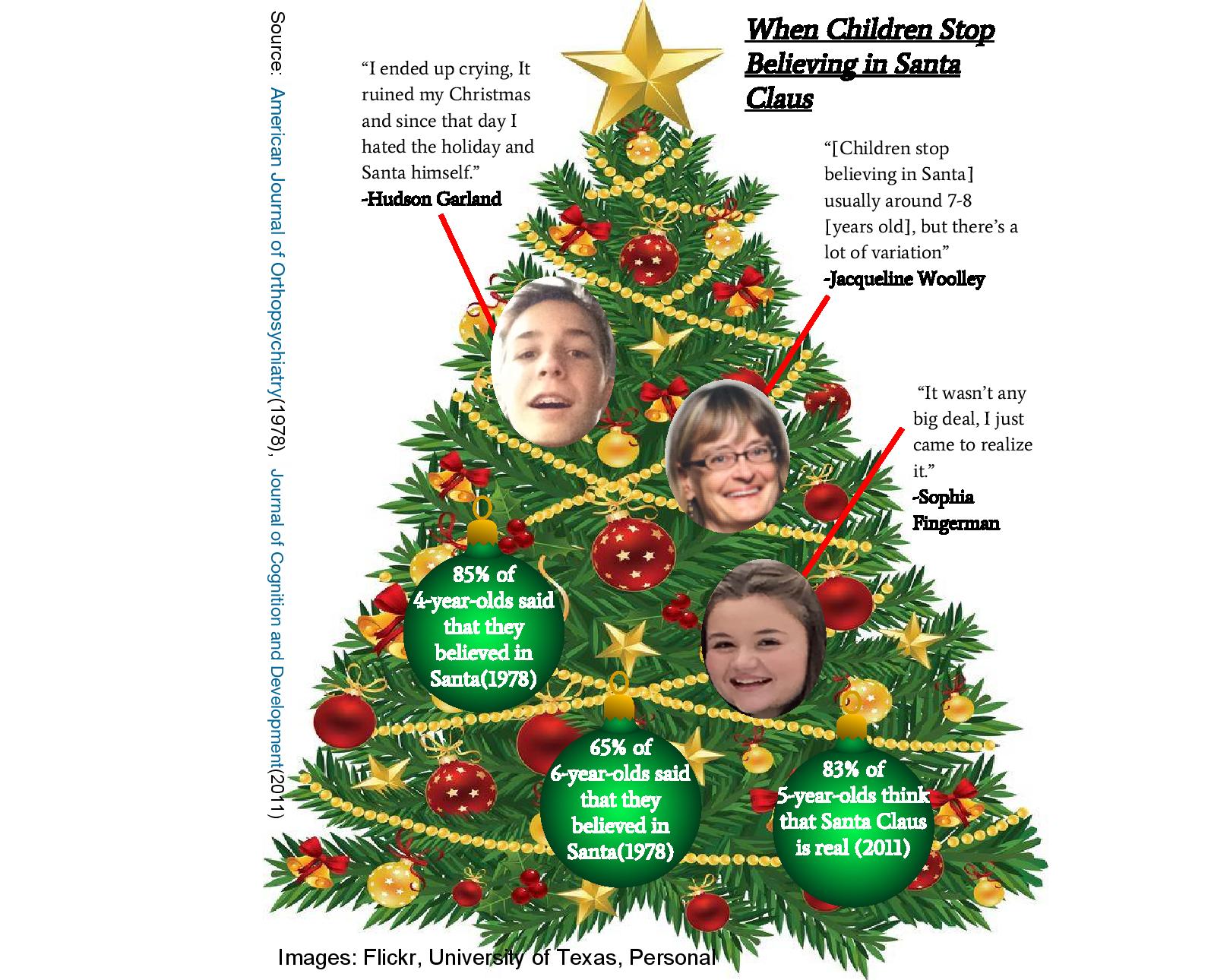

Patrick and his mother Beth celebrating the holidays.

Patrick at 12 months.

Patrick, fifth grade, and his sister Caroline on Halloween.

Patrick and a friend on Halloween at Da Vinci.i

Patrick graduates from Da Vinci Charter Academy in 2018.

Patrick votes for the first time in November 2018.

Patrick in his dorm room at George Mason University in fall of 2018.

Ty Motekaitis: Difficulties with employment, housing

Ty Motekaitis, a 2005 Davis High graduate, was in the special education program at DHS. After graduation, he spent a few years at Sacramento City College. “I never got to finish it, but it’s still a great place,” Motekaitis said. Then, Motekaitis wanted to live on his own and get a job.

“We didn’t do the government programs; we just basically tried to get him in as a normal person,” said Daniela Camarra, Motekaitis’ mother.

Motekaitis struggled to find both housing and employment. He took part in a program to provide disabled people jobs working in a cafeteria, though he was paid far less than minimum wage. Camarra was furious upon finding out how little he was paid and eventually the program agreed to meet the minimum wage, though they cut his hours.

“They were paid $2.38 an hour. I’m not even kidding you. I questioned it from the start. Like, how are they not making minimum wage?” Camarra said.

His mother would try to rent apartments on his behalf, but upon disclosing his special needs, she said landlords often made excuses to deny occupancy.

Motekaitis eventually began working while living with his mother on her farm outside Davis.

“He’s the best roommate too. So clean, ridiculously clean. He’s a good human being, But just watching [him], no one wants to give him a chance,” Camarra said.

Immediately following his move from high school, Motekaitis lost the social aspect of school and sports.

“That was a tough transition to tell to Ty, ‘you can’t go to this program anymore,’ you know?” Camarra said.

However, he soon joined two sports at Sac City, allowing him to have a more social environment than the classrooms.

When Motekaitis left Sac City, he also left the teams, and relied on events like anime viewings at UC Davis for social opportunities. Additionally, he worked with his father, UCD swimming coach Pete Motekaitis, to mentor other students with disabilities.

However, Camarra believes that DHS did not prepare her son well enough for life following high school.

“Davis is amazing in protecting you. I don’t think Davis is amazing in applying super assistance,” Camarra said.

DHS has developed many programs since Motekaitis’ time at DHS, like the Workability program, classes specifically designed to prepare students for life after high school.

DHS takes steps to ease transition

In 2018, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 19.1 percent of the disabled population is employed, compared to 65.9 percent of the non-disabled population. These statistics, along with the end of involvement in a special education program can make the end of high school an even tougher transition for students with disabilities.

Stephen Smyte, the DHS football coach and a special education teacher, knows that the transition is very difficult, but believes that the Workability Program can help.

Workability places students with disabilities in community jobs after they go through the typical application process of creating a resume and an interview. They work the jobs as any other employee would, though they have the support of the program at the high school to help them with any problems they may encounter.

The special education department also offers classes that help with career and interpersonal skills, in an attempt to prepare students for post-secondary life.

Smyte also believes that the current emphasis on extracurricular involvement at DHS really helps special ed students develop social skills that will help them throughout their lives. According to the most recent review by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges accreditation process, 83 percent of special ed students at DHS are involved in non-academic activities like sports, clubs, arts and music.

Additionally, Debbie Press, who works on the workability program, checks in on students during their first year out of high school to see what they’re doing and refer them to an agencies that may help them.

“We ask them, ‘are they working? Are they going to school? Do they need help with anything?’” Press said.

Smyte believes that the right path for each student following DHS is different, and wants to support students no matter what they and their family choose.

Andre Clark: Staying close to home

Andre Clark, a 2018 DHS graduate, went through special education courses and support during his time in high school. Upon graduation, Clark did not go away to school, but rather stayed nearby and now attends Sacramento City College.

While his daily life is similar to what it was like at DHS, Clark felt that the transition from high school to college “was rough.”

“College can be stressful and upsetting at some times because people there are kind of different from high school,” Clark said.

Though the change from a structured and supportive social setting in high school to the more independent one in college was difficult, Clark found friends through involvement in clubs. As an ambassador for the LGBT club, he works to help and support those who identify as gay, lesbian, transgender or bisexual.

Additionally, Clark continues with Best Buddies, a club focused on promoting inclusion for students with disabilities that he also participated in at DHS. Once he joined the college-level Best Buddies, Clark noticed an improvement in his social life at Sacramento City College.

Analeah Elohim: Pursuing passion

Senior Analeah Elohim makes her own jewelry and sells the wares to fellow students at DHS. While unsure of what she will do next year, she is exploring career options related to her craft-making.

Patrick Foraker: “The cliff”

Beth Foraker wanted social opportunities for her son, too, as well as academic growth. She poured hours upon hours of research into looking into what Patrick’s next step would be. She wanted to be sure they were pursuing a path he was interested in, not just something she pushed him into.

When Beth toured a special education program at George Mason University with Patrick she knew this was somewhere he wanted to be when at the end of a long day he was pushing to go to dinner with other students.

Patrick’s father John Foraker was still unsure about sending his son to a program in Virginia, believing that it might be best for Patrick to keep him closer to home. However, when John returned to see the program for himself, he broke down in tears seeing Patrick participating and being fully included at the preview day, and knew the program would be perfect for his son.

At GMU, Patrick lives in an integrated dorm with two other students in the Learning Into Future Environments (LIFE) Program. He also lives with one George Mason student who is not a part of the Mason LIFE program.

In addition to inclusive living, Patrick takes classes with Mason LIFE students as well as regular university courses. Counselors can help him find jobs and internships to explore his career interest of becoming a movie director.

To Beth, this integrated living situation is one of the keys to creating an environment to support Patrick and other students with disabilities. Not only is Patrick able to have an academic environment, he is also integrated into a social environment and community.

“Someone with an intellectual disability is socially isolated. They just really are,” Beth said. “If they’re embedded in the community for four years […] they can really form a network.”

With her son thriving in the innovative program, Beth Foraker is now pushing for UCD and universities all over the country to create four-year programs like George Mason’s.

“You cannot tell me […] there’s not people with amazing talents that could be contributing amazing things to their communities,” Beth said.