Reshaping religion: how the pandemic has impacted students’ faith

By Allyson Kang,

BlueDevilHUB.com Editor-in-Chief–

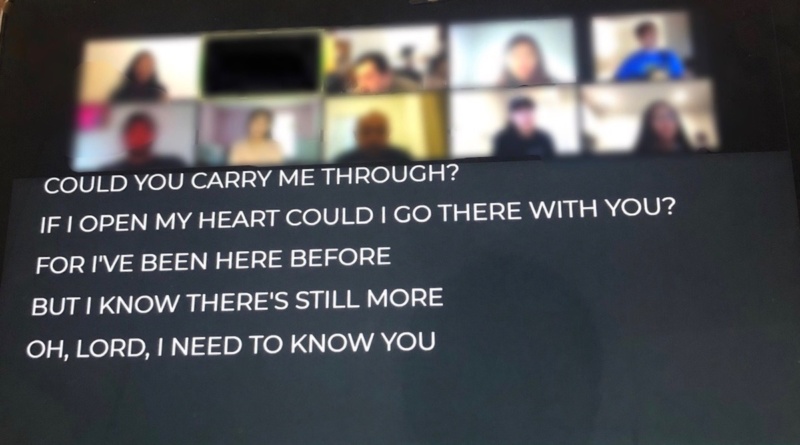

PHOTO: The Davis Korean Church youth group, composed of secondary school students, sings a praise song together over a Zoom meeting.

In the era of distance learning school and Zoom playdates, another core community meeting has had to move online: religious gatherings.

From Muslims to Christians to Buddhists, many Davis High students have modified their religious practices to follow health recommendations. Some have struggled with their personal faith; others feel that not much has changed.

- The Loss of Community Connection

- Prayer: A Powerful Practice

- Suffering and Inspiration

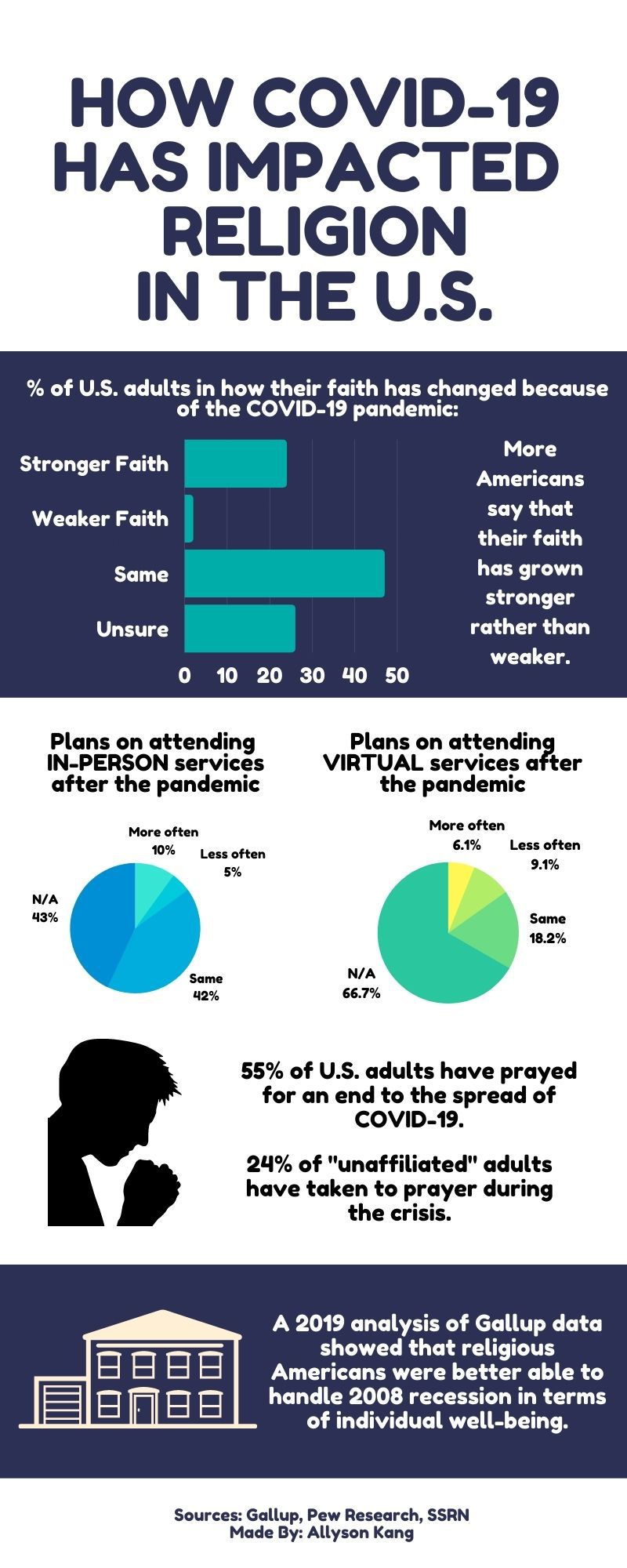

- Impacts in the U.S.

In Yolo County, indoor religious services are currently not allowed. Online worship, on platforms like Youtube livestream or Zoom, and outdoor services have replaced traditional community gatherings. The loss of community worship has led many Davis residents, including Davis High students, to feel disconnected with their faith.

Meaghan O’Keefe is an associate professor of religious studies at UC Davis. In her experience, she’s found that “for many people, communal worship is incredibly important [...] For [example], if you've ever been to a big Evangelical Church, you have an amazing sound system, you have a band, and it's this incredible communal feeling,” O’Keefe said.

Senior Elise Kang is Christian and a member of the Davis Korean Church. She attends her youth group through Zoom.

“I think I lost some of [the] community I had back when my youth group was in person. I felt like I could talk about my faith more when I am face to face with fellow Christians,” Kang said.

Senior Marley Adler is a youth member of the Jewish Congregation Bet Haverim. During the pandemic, she has attended her group’s religious events virtually, from a Zoom bar mitzvah to Shabbat services over Facetime. The transition has also led her to feel disconnected with her congregation.

“One of my favorite parts of services is sitting in the synagogue with my friends and family around me, all singing the same songs that we have known since we were little,” Adler said.

Now, because members are all muted and isolated, “I don't get that same sense of unity and connection.”

Senior Omnia Ali, a member of the Islamic Center of Davis, has also missed the sense of connection in her own religion. Although one of the key parts of Islam, the five prayers a day, is individual, Ali has still felt the impact of not being able to meet with others of her faith.

“When you're [...] around people [...] that you know share something with you, whether that’s religion or the same values as you and the same language [...] not having that is definitely very impactful. You feel very disconnected with yourself and your identity,” Ali said.

On the other hand, senior Faith Vu believes that her and her family’s connection with Buddhism has not significantly changed. She considers Buddhism to be more of an individual religion from her experience attending various temples in Sacramento and on vacation.

“Even when we went to the temple, everyone just went at their own pace, no one went together. It’s not like church, where everyone comes [together],” Vu said.

Prayer is a foundational part of many religions and often a practice people turn to in times of need. According to a Pew Research study released on March 30, about 55 percent of American adults have prayed for the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Davis, virtual community-wide prayer movements have been taking place, like the Christian prayer movement called “PrayerForOurKids” during Sept. 14 to 18.

“In a situation like this where we have so little power [...] you feel really helpless [...] People find that they want to do something, and that thing you can do sometimes is pray,” said Meaghan O’Keefe, an associate professor of religious studies at UC Davis.

Senior Shruthi Karthik practices Hinduism, which focuses heavily on prayer. She and her family “pray every day that things will get better in the world,” Karthik said.

However, her religious practices haven’t changed significantly. Even prior to the pandemic, Karthik and her family followed their religion at home, from praying to cooking dishes for special occasions.

The temple she attends currently hosts virtual prayer sessions, which don’t have “the same feeling as being in the temple, but it's better than nothing,” Karthik said.

Senior Faith Vu, who practices Buddhism with her family, noted her parents’ continued dedication to prayer during the pandemic. “They’ve prayed in my backyard with the incense but they haven’t gone anywhere else,” Vu said.

Senior Omnia Ali and her family follow Islam. Ali has seen drastic changes in prayer in her religion, mostly from the loss of nightly community prayers. When the Davis mosque opened up briefly, people prayed six feet apart, which was “really weird because usually people pray foot-to-foot, shoulder-to-shoulder.”

Ali added that it is believed that “praying together just has more reward.”

From illegal gatherings to community soup kitchens, the U.S. has seen the opposite extremes of religious actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The response reflects the more personal struggles of people with their faith in times of crisis.

“It’s a really individual thing. For some people, difficulty makes them lose their faith; for some people, it deepens it,” said Meaghan O’Keefe, an associate professor of religious studies at UC Davis.

Senior Elise Kang, a Christian member of the Davis Korean Church, feels like her faith has been “inconsistent.”

“There are some days when I think that this [pandemic] will not end at all and that the God I worship will not stop it at all. Other days, I think [...] that my God will stop this pandemic,” Kang said.

O’Keefe relates the response to the problem of theodicy, which is the question of why a good God would allow for evil in the world. When people are sick or struggling financially, some attribute it to being part of a greater plan or punishment.

However, the “The Evils of Theodicy” by Terrence Tilley, says "none of these [answers to theodicy] seem right [...] And that’s the only answer to the problem of theodicy, the problem of suffering. That we don’t know, but small and good human acts, that is what makes it bearable and that is the presence of God in the world,” O’Keefe said.

One example O’Keefe found inspiring was the Sikh soup kitchens in Sacramento.

Other Davis High students believe that while the pandemic has transformed their religious practices, it has not greatly affected the strength of their faith.

“To be honest, I think it's had very little impact,” Muslim senior Omnia Ali said.

“The pandemic has not really changed our faith in any way but it has changed our practices,” Jewish senior Marley Adler said.

Adler and her family have focused on ways they can adapt and continue to follow their religion.

“Since we can't do all of the things we used to, my family makes sure to keep participating in practices we can do, like family Friday night dinners and lighting the candles for Shabbat. We have also baked homemade challah,” Adler said.